I sit naked on my bed and listen to the soft scratch of the wind as it slides against my net curtain. The net rustling and moving as the breeze slants gently against it. It’s still hot like a motherfucker. Scorching, blazing heat that drives out all sense of reality, of propriety. How many other times would I sit naked and alone in my room, wondering whether I should try and grab some time standing in front of the open doors of my fridge. Instead I grab an ice cube from the rapidly melting pile by my thigh and slowly roll it across my chest. Sharp intake of breath as my skin, which feels as if it’s on fire, is quickly cooled. For a few seconds while I rub the ice cube along my flesh, I feel relatively stable and normal. But not for long, as the heat of this month overpowers it and leaves me once more feeling hot and oppressed, with nothing I can do about it.

My eyes are slits, my breath is shallow. I drop the cube back into the bowl, what’s left of it anyway. Smearing the remaining liquid on my fingers across my face. Shift my butt on the towel spread there. It’s early evening, just gone half six and I’m wondering why it isn’t getting any cooler. The sun’s sliding down over the horizon and my window’s as open as it can be. But I still can’t find any wind. The Isley Brothers were chatting shit about summer breeze. Fuckers sure didn’t live in London.

I get tired of sitting on my arse, so I stand and stretch until my spine creaks and pops and my chest makes an almighty cracking sound. I haven’t done shit all day. Working a three-day week gives you a different outlook on things. Lean against the open window and look down out onto the grass beneath. It’s too small to be a common and not big enough to be a park. I remember cutting across there with the other kids, still in school. So much energy, stripping off our shirts and screaming like madmen. Voices raised so everyone could hear. That warbling rising wail that we produced as we ran passed down from generation to generation, so now kids who I don’t know do it. It was a badge of identity, a way of belonging. So we’d play football into the night, the sun slipping away, the light fading. Mothers leaning out on balconies yelling for their offspring to come home. I was one of the few, the brave, the few whose mother wouldn’t call for me. We knew that we were in deep shit. So we’d stay out as long as possible, delaying the inevitable. Those kids whose mums would call, their voices becoming more and more frantic as the night wore on, knew they were safe. They could tell just how long to stretch it, until just when she was about to come down and look for them, they would appear out of the dark. Teeth grinning and duck out, heading home. But us whose mothers didn’t call, we never knew whether our mums would let us slide or make us pay for keeping them in suspense and staying out so late when we knew what time we were supposed to come in.

My mother wasn’t one to beat me often, but when she did, I remembered it. Her accent would thicken, become more pronounced, that Scottish brogue stepping forth. It would become just like Granny’s as her hand flashed down upon me. She’d never come at me direct, always obtusely, laterally. There’d be no shouting in our house when I was getting beat down, just me crying long and hard. My cries of anguish turning into whimpering pleas for mercy. She’d beat me fierce. The hand falling forever. Time would stop when Mum beat me. There would just be the pain across my thighs, spreading outward as my skin reddened. After the first few blows I’d stop twisting in her grasp and just stand there, trying to go beyond the pain, but unable to. And Mum, grim as death, standing there over me. She never trotted out any of the cliches that my friends would recite at school. Another black experience that white people would just never understand. They would laugh and joke, voices raised high as the tube rocked through the blackness. The bulbs above us occasionally flickering to remind us that we were in a tunnel miles beneath the earth. That this wasn’t sunlight above us, but hard, harsh, artificial lighting that could be switched off at any time, plunging us into unremitting darkness. They would laugh and the accents would come out, thick Jamaican accents, rolling forth over the roughness of our London twang.

“If you can’t hear, you shall feel.”

“What you crying for. I’ll give you something to cry for.”

Bursting into laughter at each example, a chorus of voices expanding through the carriage. Each with a new angle, a new variation on the getting-beat-by-Mum theme. I’d listen and I’d laugh but I would never add my story. Because Mum wasn’t like that. She’d just hit me cold and remorseless. No sound coming from her except just before the first blow would fall, when she’d tell me why I was getting beat. With her accent growing stronger by the second.

After the beating she would send me to my room and I’d dive onto my bed and cry into my pillow, and sometimes I could hear her crying out in the hall. Her sobs muffled because she had her face in her hands, and I’d wonder what’s she crying for, I’m the one who just got beat. My heart would harden and I’d pray that I was adopted and that soon my real parents would descend like angels to take me away from this living hell.

But shit like that don’t happen, so I’d go to sleep and wake up in the morning and everything would be like it never happened. Life just rolled on. Summer. Winter. School. Mum would make breakfast and then duck out to work, and I’d sit in front of the TV for a while watching Why Don’t You? before ducking out for another day running through the long grass. Playing British bulldog, screaming, yelling, sweating. Knees scraped, my trainers talking to me. Scarred, bruised and tired, but triumphant. I would return aware that I had to be on time this time. Slip in just before my curfew and watch while Mum pulled my food out of the oven.

***

I watch the shadows lengthen, the softness that has enveloped my part of town. The light being cast no longer defining, forcing things apart, but now blurring the edges, making forms and shapes melt together, soft like Haagen-Dazs that’s been left out overnight. The sky now a gentle pink, the cutting blue that it is during the day spooling into the pink all around.

I stand by the window for a long time and just stare, my eyes becoming unfocused, seeing but not seeing at the same time. Two states of being combined at the same time. Time passes slowly, how much I’m not sure. A minute, fifteen maybe. I can’t tell by the sky or the amount of light that passes by my eye.

Lean out of the window and stare at the brown grass beneath, feel it flex and bulge as if the floor is aware of my looking at it and is changing its perception of itself. Imagine myself falling towards it, falling, falling. Aware and awake of every second of my flight. My velocity increasing, pushing me into an inevitable collision.

I’m snapped out of my staring game with the earth by the coarse sound of the phone ringing. It coughs loudly into the silence, unwilling to be unnoticed, forcing me to pay attention to it.

“Hello…”

“You ready?”

“Once I put on some clothes.”

“Hurry up, I’ll be there in fifteen minutes.”

“No, you won’t.”

“Time me. Later.”

“Later.”

I hold the phone for a few seconds after Iago’s put his end down. Hearing the dead tone, the dead air between us. Phones are so impersonal, detached. You have no idea what’s going on inside the other person’s head. What emotions they’re feeling. Whether they’re happy or sad, or what. You’ve just got to go on the sound of their voice. No eye contact, no facial expression, just on the words that they say to you and the tone that they say those words in. So much is open to misinterpretation, misunderstanding.

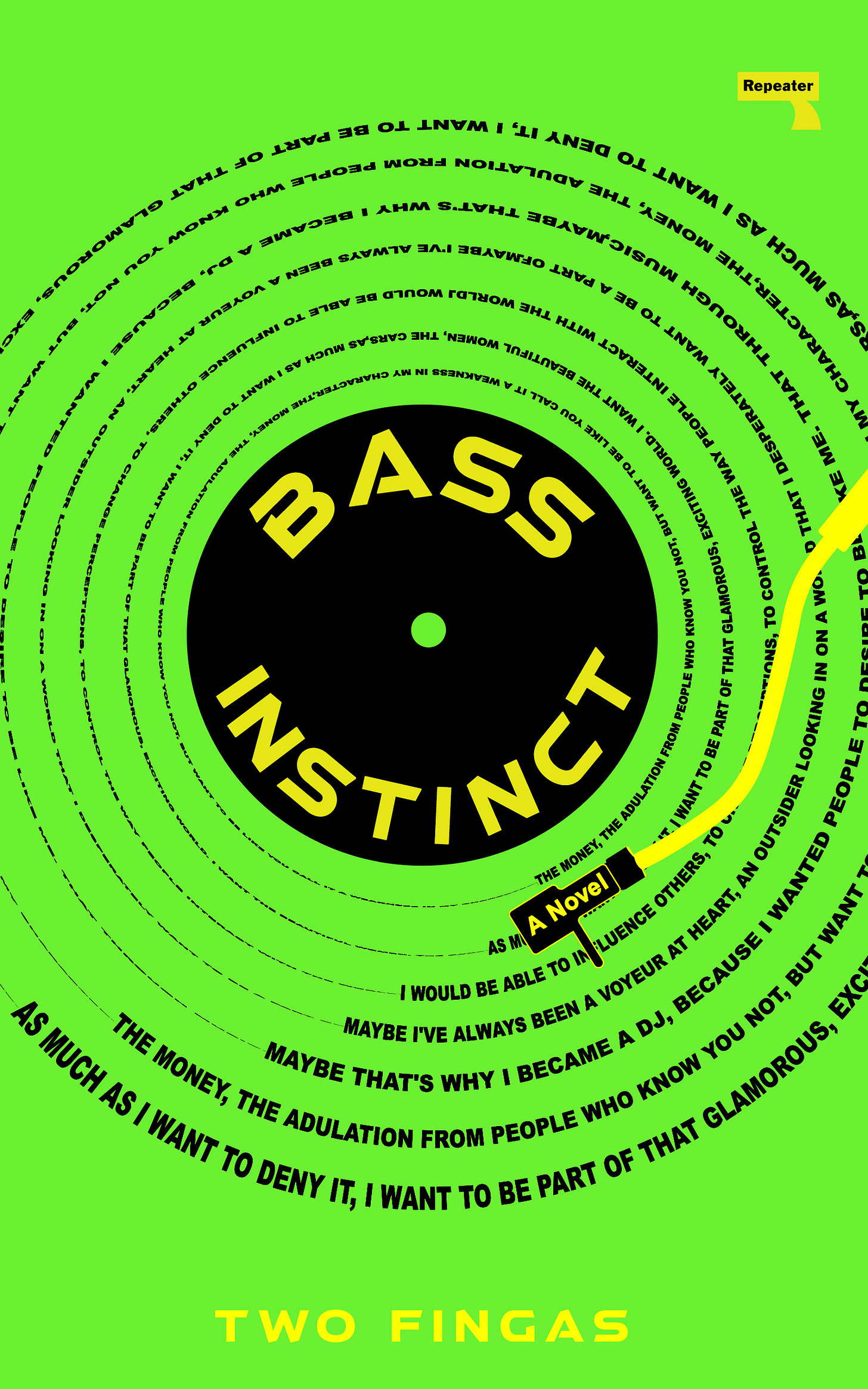

I put the phone down and ponder on what I should wear tonight. I know what I’m going to play; all of my records are stacked and boxed in their flight cases, all ready to go. Just waiting for me to pick them up and shove ’em into the back seat of Iago’s Mini. Look over to my clothes rail standing up against the wall. Stuffed full of shirts and tops, jeans and jackets. To brief or not to brief that is the question. Pull out some boxers and drag them on. Pull on my Jean shorts and then look to my wall, where they hang. The special wooden pegs varnished and gleaming on the bare white wall. Their backs to me, the numbers the same even though the colours are different. When I put them on, I know what I was put on this earth to do. I know who I am and why I am. No doubts enter my mind. I slide my hand over the fabric, lifting it to my face and inhaling of the fragrance. The fabric’s starting to fade, but still, to me, it has a lustre all of its own. Brazilian shirts have a magic that no one can deny. I pull it on and feel reborn, the yellow fabric taking on a luminescent glow, everything spins into slow motion, Raging Bull black and white, except for the glowing Brazilian shirt. Slip my arms through the sleeves, the fabric rubbing over my bare nipples. Pull my head through and roll it down across my stomach, knowing that I am Eder, the boy from Brazil.

Push my hands into the deep pockets of my shorts and play with my bollocks, then pull them out as I sit to pull on my Air Max. The wooden frame of the bed comes courtesy of Granny. I broke the old one jumping on it, pretending to be spiderman or something, had to sleep on a mattress on the floor for ages until Granny came down for a visit, bringing with her some geezer from the old country who was older than she was. Wrinkled like an old tomato, wizened and bent over. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw him ’cause he looked like a leprechaun, even though he was Scottish, with a twinkle in his eye and an accent to die for. A bag of tools held gently in his callused hands, but his hands had these long fingers that went on forever, delicate looking, and they seemed to move even when he was holding them still. They reminded me of old Chinese couples practising tai chi in the park of a morning, all smooth and slow, like moving through water.

Granny just pulled him in and set him going. He disappeared for a few hours, then reappeared like some sort of magician. No puff of smoke, no flash of light. Just now you don’t see me, now you do. And he’s there standing in front of me with a shitload of wood on his back and commences to build me a bed. It was just like magic, but not that bullshit David Copperfield “I’m a magician and I’m going to let the whole world know it.” But a quiet, confident magic. A magic you can believe in. That makes you believe elves and pixies do exist. Granny called him Mr Bartholomew; nothing else, just that.

Check that my legs are creamed properly. I gotta be creaming my skin 24/7 ’cause I must have the driest skin in the universe and there is nothing worse than seeing a black man walking down the street with white elbows, knees and ankles. Sorry-looking sight, and now that it’s summer, that shit can’t be done. Run my hand across my bald head and breathe deep. Step to my set and pull my spliff holder and lighter off my deck. Flip it open and pull out one of my readymades. I try not to let ’em stay in there for too long, a day or three at the most, otherwise they get dry and harsh and burn the fuck out of my throat. Light one up and sit back into my director’s chair, the one with my name stencilled in on the back in big black marker. Blow out smoke and watch it spiral. I love watching smoke, watching it drift towards the ceiling. Taking up space, fogging a room until you can only see murky forms sliding through. But more than smoke I love the scent of weed, so sweet, so potent. Nostrils catching it, getting stoned on it and you’re not even smoking, just sitting in the same room.

“Fuck.”

Iago’s leaning hard on his horn again. Shattering the silence of the evening. I hate when niggas be leaning on the horn instead of just taking their lazy selves up the stairs and knocking on a man’s door.

“What do you want?”

I’m leaning out of my window, shouting down at him as he leans on his Mini as if he’s some sort of Mac Daddy pimp from the nineties.

“You coming down?”

“I told you already not to be leaning on your horn.”

“You ready?”

“Am I wearing my shirt? If I am, then I’m ready.”

“Hurry up, I got to pick up Dean.”

Look around for a second, disorientated. Grab my keys, my sunglasses and the most essential part of my ensemble: my spliff holder and lighter. Shove them into various pockets, then spend the next few seconds fishing out my sunglasses and putting them on. Got to look cool in the summertime. Pick up my records in their shiny silver boxes and heft ’em downstairs. Shove my head round Mum’s door.

Mum’s reading a book, some heavyweight text. She’s always reading someone, Dostoevsky, James Joyce, Tolstoy, Dickens. Just full on, no sellout works. She’s laid out on her bed, wearing some Russell Athletic sweats that I brought for her. The small reading glasses she wears perched on the end of her nose, a jug of her special brew homemade lemonade beside.

“Where are you going?”

“Playing out, it’s Josephine’s birthday.”

“You be good now.”

“Yeah, I’ll see you later.”

***

Iago’s got the Mini turned around and is sitting on the bonnet. Iago’s my best friend; we been together since we were twelve. Same class in school after I transferred. Me, Iago and Danny, the three musketeers. Iago’s got four sisters, two older, two younger, and we’ve decided for friendship’s sake that I’ll be leaving them all alone. But I have to say that they are fine, fine as may wine. At times it’s difficult indeed to just let them be. Which is one of the reasons I don’t go round to Iago’s as often as I should. Being in his house is enough to drive any man insane. With all the hollering and yelling, half-naked flirting with you.

First there’s Esta, she’s the oldest, twenty-six, went to school with Juli, she’s just about to finish a degree in accounting, somewhere or another. Big hair, big laugh and looks that’ll cut you in half. She’s also got a hard tongue on her, which can lead to some nasty bruises on the ego.

Then there’s Chandler, Iago’s twin. She was born a minute or so before him. She works for Barclays. I told her to move to the co-operative bank because Barclays is the kind that’ll stiff you. But like all the women in Iago’s family, she’s got a mind of her own. But she is fierce, just unremittingly hard. All sharp edges and places to get cut. I don’t know why she’s so hard; Iago ain’t saying, Chandler ain’t saying, so I’m left wondering.

Next is Vanessa, seventeen. Now she’s deadly, and she wants me, which isn’t good, not good at all. Doing her A-levels, she wants to be an architect or something. She told me that she was out for a man with a fast mouth and a devil-may-care attitude. Her words, I assure you.

Then there is Nola, thirteen. Youngest of the Styles clan and doing those teen things: posters, song lyrics, crushes. She’s got that colt-like grace and awkwardness that comes with being unsure what your body is about to do next. But her mind’s as sharp as all the others. Just cuts to the chase and takes you out if your shit is weak.

Iago, like the rest of his family, is tall and rangy; long, as my mum would say. Obviously no one stepped over him as a child. He’s dark, as dark as I want to be, obsidian. He attracts light, his dark skin absorbing it. He’s got these thin-ass eyebrows which are prone to being raised in disbelief, and eyelashes which his sisters constantly tease him about. His eyes are dark, prone to filling with tears or becoming grim with ill-concealed anger, and his nose has flaring nostrils which are emphasised by the big silver hoop which pierces the left one. His lips, soft and pouting, often curling into a slow smile, reveal white teeth that wouldn’t be out of place in a Colgate commercial.

He’s leaning on his pride and joy as I come towards him: his ’66 Broadspeed GT. It’s a Mini coupe which looks like a Mini hatchback, or if you’re me, a duck. Alloy wheels, low-profile tyres, lowered suspension and a big fucking engine. Well, big for a Mini anyway; 1400cc fuel-injection and a five-speed gearbox. How he manages the insurance on it I will never know. Iago believes his car to be a jet fighter and drives it as such, pulling on his aviator glasses and doing his Tom Cruise impression.

“I feel the need, the need for speed.”

He’s been hauled over so many times it has become embarrassing. But sitting in it is like nothing on earth. Wherever we go, nothing, no other car, pulls as many stares. It might just be the fact that the sound emanating from the car is loud enough to destroy eardrums at sixty paces, but I personally believe it to be the all-round class of the car. It is just so strange and exciting, not like your Vitaras or Golf Cabriolets or BMWs that every other nigga drives. It just makes a statement straight out the box. Dark metallic blue it is. Don’t ask me where he got it from, ’cause I don’t know.

“You gonna give me a hand or pretend you’re Huggy Bear?”

“Keep that pimp shit to yourself, I ain’t wearing flares and platforms.”

“But you got the Afro.”

“This is my Black Panther, militant-nigga-on-the-real-deal Afro.”

“If you say so.”

“Just get your shit in the car.”

“No, not shit. Records. R-E-C-O-R-D-S. Records are not shit, records are precious articles of our society, a chronicle of black life.”

“Yeah, yeah, just get them in the car.”

Look at him as he loads up the records onto the back seat and into what little space he calls a boot. His Afro rubbing the doorframe, he hasn’t combed it for a few days and it’s just standing up on his head. His sunglasses lost in a forest of hair. Dressed as casually as I in his Michigan basketball top with Chris Webber’s number on it, dark Adidas shorts and his Reebok classics.

Jump into the car and slide myself into the movable racing seat from Recaro that folds forwards so others can get into the back. Iago adjusts his rearview mirror, kicks the car into gear and slides it dangerously out into the street. He flicks on his set using the little control column by his steering wheel and cranks up the volume. Now, for a man who purports to be a DJ, I find it strange that he doesn’t have a set in his house. But no, he fills his car up with the darkest set known to mankind. People know we be out, because that driving bassline does come before us. The front of the car’s a mess of tapes, some in cases, some not; some labelled, most not. Iago spends most of his time driving searching for a specific tape, which he never finds. Well, not while I’m in the car.

“Listen to this, I hooked up another bass bin.”

A flick of a switch and I’m encased in sound like a strait jacket. The bass is enough to deafen mortal men, but we be niggas, so we just nod our heads and feel our hearts flutter at the bass’s touch. Nod my head to “Buck ‘em Down,” the remix with the sung chorus.

Buck ’em down

buck ’em down, buck ’em down, buck ’em down

buck ’em down…

I sing along, then Iago comes in with his rich tone. I’ve never been able to carry a tune, so I always feel a pang of envy whenever anyone else can. Iago’s sliding in and out of traffic, heading towards Dean’s, an old school friend, one of the funkiest white boys alive, who’s the living into jungle. Got his own little set-up in his room, sampler, keyboard, decks, Cubase system on this souped-up Mac and a whole load of extremely technical shit and wizardry which I should be into, but at this moment just can’t get my head round. Iago stomps his foot hard on the brake and the seatbelt digs deep into my chest. He’s cutting in and out of gaps I wouldn’t even attempt on my bike. The engine revving, revving, revving. The back end shaking as he puts the power down. Hand gripping the short-shift gearstick like it’s Daytona or something. No movement of the arm, all wrist. Slap, slap, slap. Fourth, back to second. Third hard into fourth, even harder into fifth, and flies are being sucked to their doom onto the windscreen.

My arm trailing out of the open window, dipping my hand into honeyed waters. Just trying to forget for a second the futility of this life. Born to die. Same shit, different day. If I believed in God I’d be screaming at him by now, asking, Why is the world this way, why? All I’ve got is my bike, my set, my records and Iago. I don’t count family, Mum and Juli and Granny. Family’s always there, they are just family. Love them or hate them, they are family, with you evermore. Friends are something else. You choose them and you can lose them. There are no special bonds that tie you to them. You choose to be friends, and that is the magic of it.

See the orange blobs float past from underneath closed lids and wonder why I’m so pessimistic. Life ain’t nothing but bitches and riches. But who am I fooling? I ain’t a rude boy, and I don’t live in Compton, South Central L.A, the Bronx, Staten Island, Brooklyn or anywhere else in the States. Just me and South London. You ain’t gonna catch me in no camo gear, I ain’t part of Smif & Wessun or Mobb Deep. No cross colours, string vests or ripped jeans. I ain’t called Buju Banton. Just Eder the boy from Brazil in his golden top in the wilds of South London.

Rub my eyes and stretch and try not to knock Iago in his head. Squint at the clock in the dash: it’s half eight. Iago takes a corner hard, racing changes. Look out the side, see the river flashing past. The lights rippling reflectively across its surface. Balls of light, glowing luminously, hanging there. Streaming past, bleeding one into the other. I love the day, but the night is when I feel most at ease, most at peace. A subconscious thing about not being black enough, not being dark of skin. In the dark, pigmentation doesn’t matter, everyone’s black. I fear that within my soul I am not black enough, that’s why I surround myself with so much blackness — Iago, my records, my attitude — to reinforce my own blackness in the face of those with nothing to prove. But nothing’s ever that simple. What is? And I sit here in Iago’s speed machine with my head feeling as if it’s about to burst.

Iago brakes hard and we’re at Dean’s. Stopped in front of a tower block. Get out and travel up in the lift. I stop counting once we get past fourteen and just stare at the silver interior, not like the lifts on the circuit. You’d never find a lift that clean here. Step out on the twenty-fourth floor and walk down to Dean’s door. From inside can be heard the deep sounds of some dark bassline, and I feel my head just nodding along with it.

Dean pulls open the door, a wave of smoke rolling over us as he stares out, a smile on his face and a spliff clamped between his lips. His long blond hair pulled back into a ponytail. He’s decked out in some grey shorts, a green surgical vest and a pair of Timberlands that he’s wearing without socks.

“Hey, how you two doing?”

We hug, first Iago then me. It’s good to see Dean. I haven’t seen him in a while. He kinda just drops off the face of the earth. When Dean isn’t holed up in his yard making jungle tracks, he’s an engineer in a studio in the West End somewhere. Helping some up-and-coming pop act remix its latest tune. We step inside and the beats just flying at you. He’s got speakers hooked up everywhere. Surprisingly, it’s light inside and tidy. Most people, upon seeing Dean, believe it’s going to be a sty. We all tramp down to the nerve centre of this operation, the bedroom. Where all of Dean’s fancy gizmos are kept.

“You ready, Dean? We ain’t got much time.”

“Yeah, I’m sorted, just got to get my jacket and some skins.”

He potters around in his room for a second, pulling on a faded jean jacket and sliding a pack of Rizlas into his jacket pocket. He bends down and grabs his box of records, handing his spliff to Iago, who draws deep. Takes a quick look around.

“You got everything?”

“Shit, almost forgot.”

Ducks over to his table and pulls out a tape, a nice metal tape that if I remember rightly costs a tenner a go in all good electrical stores. Waves it in front of his face as we walk out the door.

“You have got to listen to this.”

***

Iago drives fast, it’s like being on a rollercoaster, you don’t know whether to scream or to cry. So instead you just hold on for grim death. After a while you get used to it, but the first couple of times it’s really fucking scary. Now, if you’re Dean and this is your first spin around with Iago for a long time, the way to get away from that feeling of fear is to be smoking pure weed spliffs. When he passes it forward and I take a toke of it, I can feel my head slowly disintegrating. Eveything’s just slipping away, and I’m surprised by how quickly it’s got to me.

Dean leans forward.

“You’ve got to listen to this.”

I take the tape from his hand and slip it into the deck, Dean sits back and I turn and see him just smiling as an eerie wailing enters the car. The wailing goes on for what seems a long time before a very clipped beat steps into the arena with a demon sub-bass throbbing under it. Nod my head and start to hum the drumroll, which sounds like a variation on Apache. Then everything fades down and a Jimi Hendrix guitar break comes over the top, hard and forceful, then the living B-line just drives through and I look back at Dean, who’s still got that Cheshire Cat–grin on his face.

“This is dark.”

“Ain’t it just.”

“Let me be the first to congratulate you.”

“Thanx.”

Iago stops the tape and rewinds it so we can all listen to is again as we burn rubber down towards Gerald’s. Gerald runs the pirate station that we play on occasionally. Another old school friend. He’s got his station out on this estate in North London. We’re loathe to go there, but sometimes these things have to be done. Dean’s a regular ’cause he plays the living dark jungle set. That does tear shit up all the time. I used to go round to his a lot and listen to the new stuff that he had, dub plates, test pressings and the like. We would go round to these little shops in the back of nowhere and come back with some of the darkest shit I have ever heard and there would be like only forty or fifty copies that the guy who made it was just sending out to see what kind of feedback he would get. Just so underground and subversive. Like we were some sort of freedom fighters out to take back our country by any means necessary.

I puff deep on the weed and let it flow through me as Iago takes the tyres to the limits of adhesion. Iago’s puffing hard as well. Like the weed demon that he is. Arm stretched straight, the killer J hanging out of his lips, attached as if by magic to his lower lip. Moving every time he pulls on it. Tilting 45 degrees upwards, the end glowing, as off-white vapour flows down his nostrils out into the atmosphere. Every time I try to do that shit, I start to cough like a novice. Look out the side and see the forest of tower blocks coming towards up. The lights dotted along their heights. A random scattering. The ground floors with their security lights flooding the doorways (or they would be if they were all working).

The interior road we turn onto is filled with speed bumps to stop joyriders and excitable commuters looking for a shortcut to work from mowing down innocent little kiddies as they play.

The young ones, the wild ones, are out. Picture the estate through their eyes. The expanse of it, the despair of it. No place to go, nowhere to run. So let’s create our own fun, hang out, smoke, rebel. Rob a house, knock over a car, discover the joys of sex in a stairwell that people have been pissing in forever. Teen pregnancy. School ain’t saying shit. Hate the teachers, classes are boring. I’m not going to get a fucking job anyway ’cause I’m black and I live in England. Sit on the dole for as long as I live, stay on the estates ’cause everyone I know is here. Being a mother makes you someone, something other than just another face in the crowd. Gives life meaning, makes you somebody instead of nothing. Sit out in the sun and talk, chat about where the parties are. She’s sleeping with him. Need to get some weed, need to get some new clothes, need new trainers. House party, dress up, rub up, bump and grind.

Iago slides it to a halt, and they’re out there lounging on the steps. A quick look, a stare, gaze turns away. Nothing to be afraid of. Whatcha got? How much back up? I watch them for a few beats as the engine dies and rumbles edgily into silence. Silence which presses heavy on you until sounds filter back and I can hear their voices, hushed and quiet for the second but willing to explode into a hurricane of sound at any second. The sound of TVs high above, volumes up. A bassline driving hard, voices raised, an argument. A dog sticks its head over a balcony and starts to bellow, saliva spilling into the air. Each bark cracking across the dark spaces like thunder. The wind shafting through the buildings, soft sounds echoing as the grass rustles and the old beat-up cars which just sit, but never move, creak.

Haul myself out of the car with Dean following close behind and head over to the youths. They can’t be more than fifteen, sixteen on the outside. Cigarettes glowing ghetto red-hot. The soft flickering fluorescent light above them illuminating the backs of their heads. Graffiti, juvenile in the extreme, scrawled across its plastic casing, then along the walls. Wonder how come they’ve never been able to find any new names, how the same old ones keep coming back, year after year. They lounge across the doorway, leaning nonchalantly.

“You know which floor Gerald’s on?”

They look at me for a second, just a fraction before they answer.

“Fourteenth, red door.”

“Safe.”

Turn and head back to the Mini where Dean’s standing there with his case of records in one hand.

“Do you guys want to come up?”

Look at my watch. Getting close to half nine. Josephine will kill us if we’re late. She’s hired out equipment specially. One of her exes is doing the DJing until ten, then it’s down to us. Doing it for free, but you know got to build up a good relationship.

“Nah, we gotta go. Tell Gerald we’ll be seeing him around.”

“Yeah.”

Dean walks over to the door, puffing on his spliff. The boys look at him. He turns and waves at us before getting to the door. He hands one of the boys his spliff and carries on through while we pile into the car and Iago takes us out along the exit road.